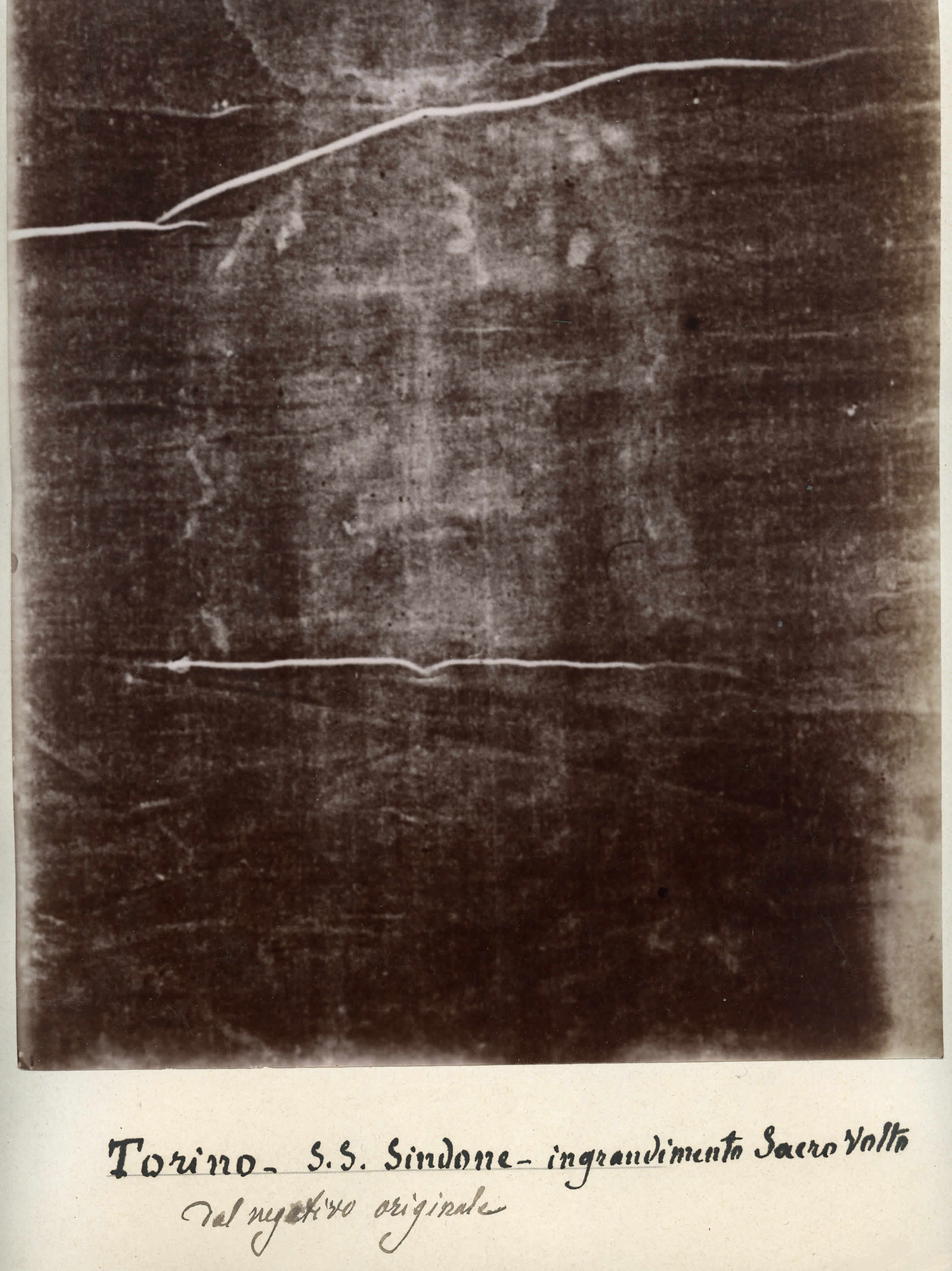

Secondo Pia's 1898 negative of the image on the Shroud of Turin has an

appearance suggesting a positive image. It is used as part of the devotion

to the Holy Face of Jesus. Image from Musée de l'Élysée, Lausanne.

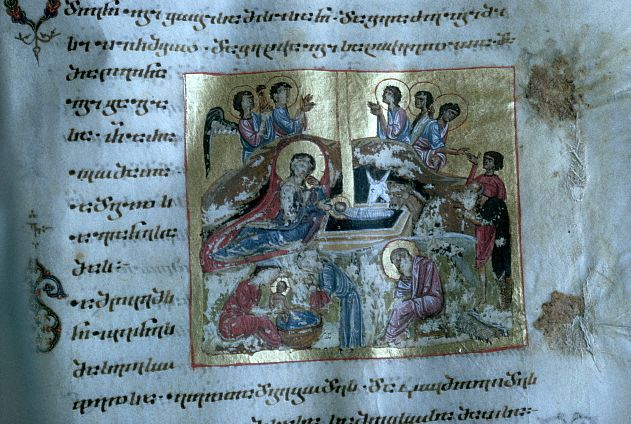

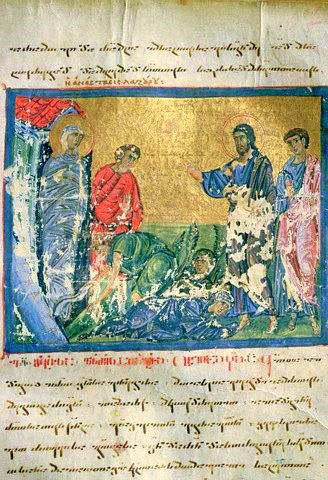

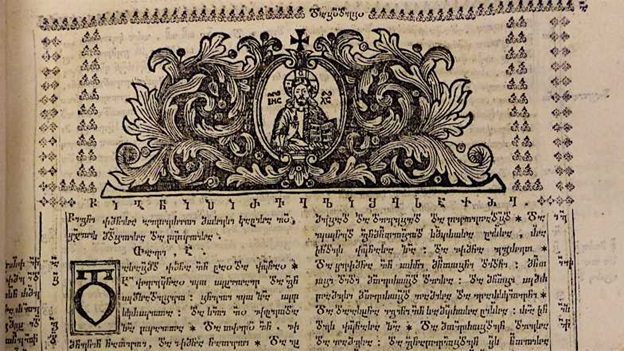

A page from a rare Georgian bible, dating from AD 1030,

depicting the Raising of Lazarus

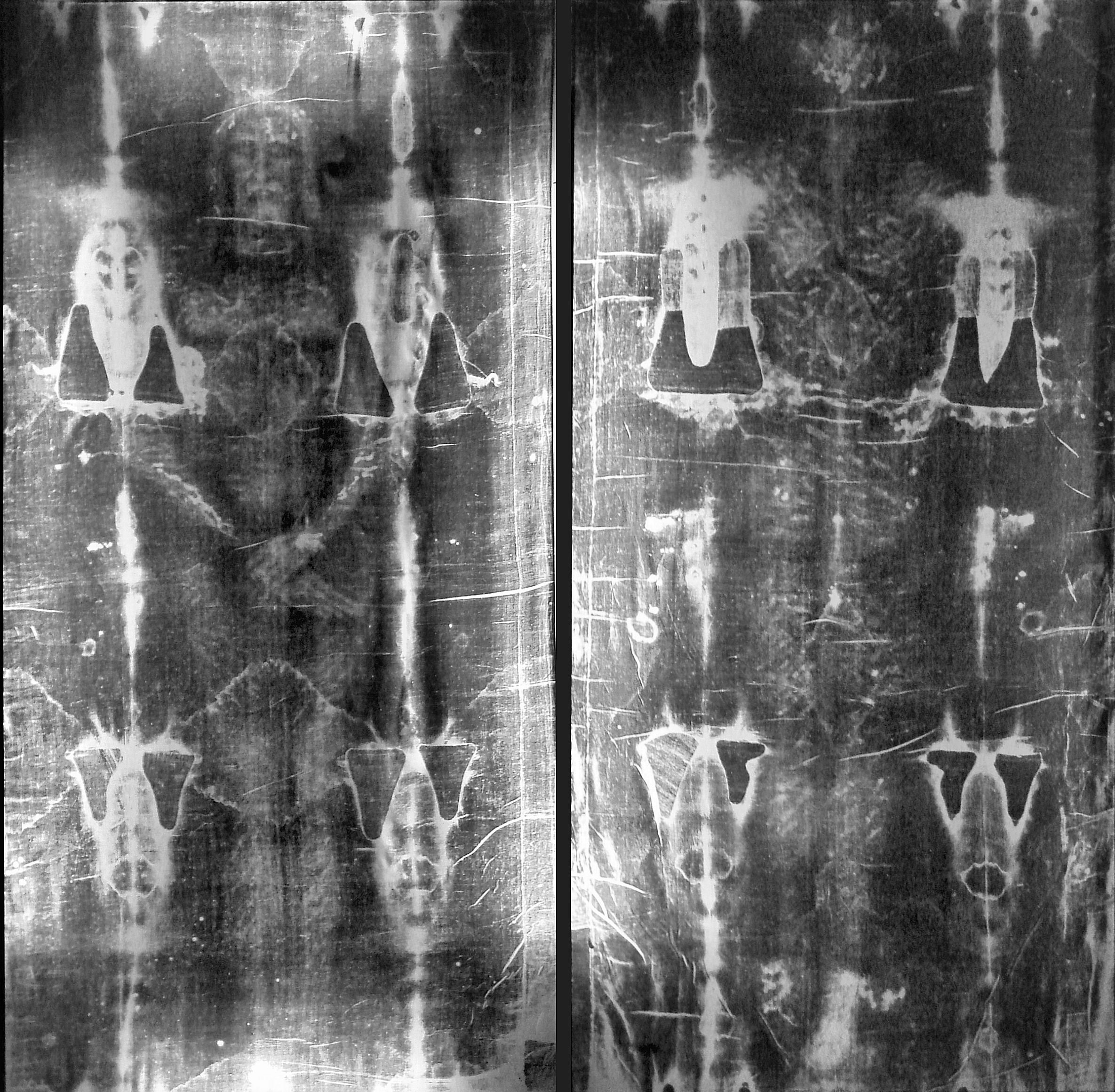

Full length negatives of the Shroud of Turin

The Shroud of Turin: modern photo of the face,

positive left, digitally processed image right

|

|

History of the Christianity in Georgia is inseparable from history of the Georgian Orthodox and Apostolic Church. The rise of Christianity had a profound effect on the Georgian principalities. According to Georgian traditions, representatives of the Jewish community of Mtskheta were present at the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and that among the holy relics they brought back was Christ’s chiton (robe) that was buried near Mtskheta. The Christian tradition also describes the allotment of “Iberian” lands to Mary, the mother of Jesus, who is considered the main protector and intercessor of Georgia. Tradition holds that Christianity was first introduced by Apostles Andrew, the First Called, and Simon, the Canaanite, who preached in western Georgia and are credited with the establishment of the first Georgian Eparchy in Atskuri (in southwestern Georgia), which is usually considered as the foundation for the Georgian Orthodox and Apostolic Church. Another apostle, Mathias, preached in southwest of Georgia and is believed to be buried in Gonio, near Batumi. Apostles Bartholomew and Thaddeus also are said to have preached in Georgia.

Historical and archeological studies reveal that Christianity spread in Georgia in the second to third centuries before it was declared an official state religion. The new religion faced a major challenge from the Sasanid Empire and its Zoroastrian religion that had a firm hold in Georgia and delayed the adoption of Christianity for decades. In the early fourth century, Equal-to-the-Apostles Saint Nino of Cappadocia preached the Christian message in Iberia (eastern Georgia) and succeeded in persuading King Mirian II and his consort Queen Nana to proclaim it the state religion in eastern Georgia around 327 (or 337, depending on a study). Western Georgia seems to have had an organized Christian Church before the eastern regions since Bishops Stratophile of Bichvinta (Pythiunda) and Domnis (Domne) of Trebizond attended the first Ecumenical Council held in Nicea in 325. By 381, Bishop Pantophilus of Kartli attended the second Ecumenical Council.

After the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon (451) established five autocephalous sees in Rome, Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem, the Church of Kartli was placed under the jurisdiction of the Apostolic See of Antioch while the Church of Egrisi was subordinated to Constantinople. The Church of Kartli constituted a part of the Antiochean patriarchy but became autocephalous (independent) in 466 when the Patriarchate of Antioch elevated the Bishop of Mtskheta to the rank of Catholicos of Kartli; the first Catholicos was Peter, who led the church between 467 and 474. In 1010, the Catholicos of Kartli was elevated to the rank of patriarch and, in 1057, the Church of Antioch re-endorsed the Georgian church’s autocephaly.

Another important development took place in the sixth century when, following the Council of Dvin, Georgian church leaders rejected Monophysitism—the christological position that Christ has only one nature—(neighboring Armenia accepted it in 506) and supported the Chalcedonian creed—which holds that Christ has two natures, one divine and one human— drawing Georgia closer to the Byzantine Empire, and later to Europe, and further from the Sasanid Persia that was more tolerant of the Monophysites. This period is noteworthy for the activities of famous Georgian theologians Evagrius Ponticus (Evagre Pontoeli, fourth century) and Peter the Iberian (Petre Iberi, fifth century).

By the sixth century, the Church of Kartli had 35 bishops and was gradually gaining its own rights and international recognition. In the ninth century, the church received the right to consecrate the myron (chrism, used in the administration of certain sacraments and in the performance of certain ecclesiastical functions), which was formerly delivered from Jerusalem. In the west, the Church of Egrisi (Lazica) was led by a metropolitan, who established his see in ancient Phasis (Poti) and was subordinated to the Patriarch of Constantinople. The close relations between the Church of Egrisi and Constantinople facilitated the spread of the Hellenistic Christian tradition in the region. In the late ninth century, the Church of Egrisi broke away from Constantinople and placed itself under the catholicos of the Church of Kartli, effectively establishing a united Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC).

Between the sixth and ninth centuries, Georgia underwent a cultural transformation as Christian monasticism flourished, leaving a long-lasting influence and stimulating a vigorous development of arts and letters. Although pre-Christian Georgian literature seems to have been destroyed in the process, new original works were created and many important religious treatises translated from Greek into Georgian. The earliest surviving examples of Georgian hagiographic literature are the Life of Saint Nino and Martyrdom of the Holy Queen Shushanik from the fifth century. The widespread construction of churches promoted rapid improvement in architecture, and gradually a unique cruciform style of church artchitecture developed, evident in the basilica-type churches of Bolnisi and Urbnisi (fifth century) and the cruciform domed Jvari Church (late sixth century). Important centers of Georgian Christian culture were established at the Georgian monasteries at Mount Sinai and the Monastery of the Black Mountain near Antioch in Syria, the monasteries of St. Sabas, the Holy Cross and St. Chariton in Palestine, the Iviron Monastery complex on Mount Athos in Greece, the Petritsoni Monastery in Bulgaria, and others. Important philosophical-theological schools existed at the Academies of Gelati and Ikalto.

The Georgian Christians had close contacts with the Holy Land and were involved in translating and interpreting Christian works; many lost original Arabic Christian texts are preserved through Georgian translations. Georgian scholars produced and translated polemical works on Christianity and Islam and original treatises on medicine, astronomy, and other fields. In the 10th century, the contacts between the Arab (Syrian) and Georgian Christian literatures faded and were replaced by Byzantine influence. The 11th–12th centuries saw the Georgian church actively participating in and adapting the Byzantine regulations and canons. The exchange of ideas was mutual, since Constantinople had a large community of Georgian scholars and theologians, who, in turn, influenced the Byzantine theology and philosophy. Constantinople and Mount Athos became the centers of Georgian Christian culture outside Georgia and produced outstanding manuscripts, many of which are still preserved at the Iviron Monastery. Frescoes, mosaic arts, icon painting, repoussé covers for holy books, and cloisonné were perfected; the Icon of the Kakhuli Virgin (10th century) remains one of the largest and most immaculate enamel works in the world. This period produced such talented scholars and theologians as Euthymios the Athonite (Ekvtime Atoneli. 955–1028), Giorgi the Athonite (Giorgi Atoneli. 1009–1065), Epraim the Lesser (Ephrem Mtsire. 11th century), Arsen Ikaltoeli (11th century), and Ioane Petritsi. Of particular importance was the activity of Grigol Khandzteli, who organized a vibrant monastic life in the Tao-Klarjeti region of southwestern Georgia.

The 10th–11th centuries saw the GOC come into possession of vast land holdings, turning it into “a state within a state” and clashing with the royal authority. In 1103, King David IV Aghmashenebeli convened the Ruis-Urbnisi Church Council that reformed the Georgian Orthodox Church. The council limited the church’s authority, expelled rebellious clergy, and expanded the royal administration into the clerical sphere. The office of the powerful Archbishop of Chqondidi was merged with that of Mtsignobartukhutsesi, chief adviser to the king on all state issues, and the new office of Chqondideli-Mtsignobartukhutsesi introduced direct royal authority into the church. Following the Golden Age in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, Georgia was devastated by the Mongol invasions and the onslaught of Tamerlane (Timur). The GOC played a particularly important role during this period when it provided a rallying point for the population, providing spiritual comfort and preserving the Georgian culture. However, political developments also affected the church. Between the 15th and 18th centuries, as the united Kingdom of Georgia was split into eastern and western parts, the Orthodox Church was ruled by two catholicos-patriarchs, and an independent catholicate emerged in west Georgia in the late 14th century.

The Georgian church was quite tolerant of the Roman Catholic church and in the 13th century, Franciscan missionaries were allowed to establish a monastery, led by Jacob of Rogsane, in Tbilisi. Later that century, the Dominicans operated another monastery in Georgia. In 1329, Pope John XXII established a Catholic bishopric in Tbilisi, which survived until the 16th century. The Georgian cleric Nikoloz Cholokashvili-Irbaki (1585–1659) served as an ambassador in Europe from 1626–1629, tried to establish links between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, and established the first Georgian printing press in Rome, where the first Georgian book, a Georgian-Italian dictionary for Catholic missionaries, was printed. In the early 18th century, prominent ecclesiastic figure Sulkhan Saba Orbeliani also traveled to Europe (1713–1716) to bring Georgia into contact with the Western powers and even converted to Catholicism in a bid to secure European support against Persia. Theatine missionaries operated in Georgia from 1628–1700 while Capuchin Franciscans existed until 1845 when the Russian authorities put an end to their activities.

After the Georgian kingdoms were occupied and annexed by the Russian Empire in the early 1800s, the autocephalous status of the Georgian Orthodox Church was abolished by the Russian authorities in 1811. For the next hundred years, the Georgian church was subordinated to the synodical rule of the Russian Orthodox Church, and the Georgian liturgy was suppressed and replaced with the Russian liturgy. In the 1850s, most of the GOC’s property and lands were requisitioned by the Russian government.

The February Revolution in 1917 provided the possibility of reviving the GOC, and its autocephaly was restored on 12 March 1917, although the Holy Synod of the Constantinople and the Russian Orthodox Church refused to officially recognize it. The restoration of the GOC proved short-lived, since four years later the Red Army invaded and occupied the newly independent Georgian republic. Throughout this period, hundreds, if not thousands, of churches and monasteries were damaged or destroyed throughout Georgia, particularly in revolutionary Guria. Inspired by new ideology, the Bolshevik authorities persecuted the Georgian church and had thousands of priests and monks arrested. During World War II, persecution of the clergy was relatively limited as Joseph Stalin sought to use the church to rally the Soviet citizens against the Nazi threat. The autocephaly of the Georgian church was recognized by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1943, but it remained under constant pressure and supervision of the Soviet authorities. Nevertheless, between 1921 and 1978, the Georgian clergy held 12 ecclesiastical councils. The GOC enjoyed a period of revival, and the Holy Synod of Constantinople recognized its autocephaly in January 1990.

At present, the Georgian church consists of 15 bishoprics supervised by the Catholicos-Patriarch Ilia II, who resides in Sioni Cathedral in Tbilisi. The church supervises 35 eparchies and several hundred active churches and monasteries.

---------------------------------------------------

Today 84% of the population in Georgia practices Orthodox Christianity, primarily the Georgian Orthodox Church. Of these, around 2% follow the Russian Orthodox Church, around 5.9% (almost all of whom are ethnic Armenians) follow the Armenian Apostolic Church and 0.8% are Catholics and are mainly found in the south of Georgia but with a small number in its capital, Tbilisi.

A Pew Center study about religion and education around the world in 2016, found that between the various Christian communities, Georgia ranks as the third highest nation in terms of Christians who obtain a university degree in institutions of higher education (57%).

History

According to Orthodox tradition, Christianity was first preached in Georgia by the Apostles Simon and Andrew in the 1st century. It became the state religion of Kartli (Iberia) in 319. The conversion of Kartli to Christianity is credited to a Greek lady called St. Nino of Cappadocia. The Georgian Orthodox Church, originally part of the Church of Antioch, gained its autocephaly and developed its doctrinal specificity progressively between the 5th and 10th centuries. The Bible was also translated into Georgian in the 5th century, as the Georgian alphabet was developed for that purpose. As was true elsewhere, the Christian church in Georgia was crucial to the development of a written language, and most of the earliest written works were religious texts. The Georgians' new faith, which replaced pagan beliefs and Zoroastrianism, was to place them permanently on the front line of conflict between the Islamic and Christian worlds. Georgians remained mostly Christian despite repeated invasions by Muslim powers, and long episodes of foreign domination. After Georgia was annexed by the Russian Empire, the Russian Orthodox Church took over the Georgian church in 1811.

The Georgian church regained its autocephaly only when Russian rule ended in 1917. The Soviet regime that ruled Georgia from 1921 did not consider revitalization of the Georgian church an important goal, however. Soviet rule brought severe purges of the Georgian church hierarchy and frequent repression of Orthodox worship. As elsewhere in the Soviet Union, many churches were destroyed or converted into secular buildings. This history of repression encouraged the incorporation of religious identity into the strong nationalist movement and the quest of Georgians for religious expression outside the official, government-controlled church. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, opposition leaders, especially Zviad Gamsakhurdia, criticized corruption in the church hierarchy. After Ilia II became the patriarch (catholicos) of the Georgian Orthodox Church in the late 1970s, Georgian Orthodoxy experienced a revival. In 1988 Moscow permitted the patriarch to begin consecrating and reopening closed churches, and a large-scale restoration process began. The Georgian Orthodox Church has regained much power and full independence from the state since the restoration of Georgia's independence in 1991.

Georgian Orthodox and Apostolic Church

The Georgian Orthodox Church (full title Georgian Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church, or in the Georgian language, საქართველოს სამოციქულო მართლმადიდებელი ავტოკეფალური ეკლესია Sakartvelos Samocikulo Martlmadidebeli Avt'ok'epaluri Ek'lesia) is one of the world's most ancient Christian Churches, and tradition traces its origins to the mission of Apostle Andrew in the 1st century. It is an autocephalous (self-headed) part of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Georgian Orthodoxy has been a state religion in parts of Georgia since the 4th century, and is the majority religion in that country.

The Constitution of Georgia recognizes the special role of the Georgian Orthodox Church in the country's history but also stipulates the independence of the church from the state. The relations between the State and the Church are regulated by the Constitutional Agreement of 2002. |